is a book by Dr, William F Pepper, the attorney for James Earl Ray.

I found it to be extremely interesting. If you would like to read this book online. It can be found at a forum website called Altruistic World Online library .

The book can be found at the following link

https://survivorbb.rapeutation.com/viewtopic.php?f=24&t=1451

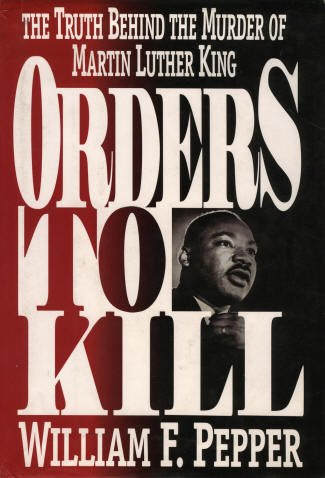

ORDERS TO KILL -- THE TRUTH BEHIND THE MURDER OF MARTIN LUTHER KING

by Dr. William F. Pepper

© 1995 by Dr. William F. Pepper

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Table of Contents:

• The Principal Players

• Introduction

• Glossary

• Photo Gallery

Part I: Background to the Assassination

• 1. Vietnam: Spring 1966-Summer 1967

• 2. Death of the New Politics: Summer 1967-Spring 1968

• 3. Memphis: The Sanitation Workers' Strike, February 1968-March 1968

• 4. Enter Dr. King: March-April 3, 1968

Part II: The Assassination

• 5. The Assassination: April 4, 1968

• 6. Aftermath: April 5-18, 1968

• 7. Hunt, Extradition, and Plea: May 1968-March 10, 1969

Part III: The Initial Investigation

• 8. Reentry: Late 1977-October 15, 1978

• 9. The Visit: October 17, 1978

• 10. James Earl Ray's Story: October 17, 1978

• 11. Pieces of the Puzzle: 1978-1979

• 12. Brother Jerry on the Stand: November 30, 1978

• 13. The HSCA Report: January 1979

• 14. Following the Footprints of Conspiracy: January-September 1979

• 15. Disruption, Relocation and Continuation: 1978-1988

• 16. More Leads, More Loose Ends: Spring-Summer 1989

• 17. James Earl Ray's Legal Representation Reexamined

Part IV: The Television Trial of James Earl Ray

• 18. Preparations for the Television Trial of James Earl Ray: November 1989-September 17, 1992

• 19. Pretrial Investigations: September-October 1992

• 20. Corroboration and New Evidence: November 1992

• 21. Making A Case: December 1992

• 22. The Trial Approaches: January 1993

• 23. The Eve of the Trial: January 24, 1993

• 24. The Trial: January 25-February 5, 1993

• 25. The Verdict: February-July 1993

Part V: The Continuing Investigation

• 26. Loyd Jowers's Involvement: August-December, 1993

• 27. Breakthroughs: January-April 15, 1994

• 28. Setbacks and Surprises: April 16-0ctober 30, 1994

• 29. Raul: October 31, 1994-July 5,1995

• 30. Orders to Kill

• 31. Chronology

• 32. Conclusion

Appendix

Notes

Acknowledgments

Index

============================================

This was just an appetizer for the book.

Please go to the following links respectively to read this book:

https://survivorbb.rapeutation.com/viewtopic.php?f=24&t=1451&start=10

https://survivorbb.rapeutation.com/viewtopic.php?f=24&t=1451&start=20

https://survivorbb.rapeutation.com/viewtopic.php?f=24&t=1451&start=30

https://survivorbb.rapeutation.com/viewtopic.php?f=24&t=1451&start=40

---------------------------------------------

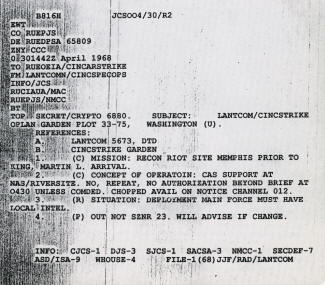

The Klan had a special arrangement with the 20th SFG. The 20th SFG actually trained klansmen in the use of firearms and other military skills at a secret camp near Cullman, Alabama, in return for intelligence on local black leaders. The earliest of such training exercises began on November 12, 1966. Some members of the 20th SFG also used these sessions for illegal weapons sales. The U.S. Strike Command (CINCSTRIKE) was the overall coordinating command (which could call upon all military forces on U.S. soil) for the purpose of responding to urban riots in 1967-1968. At that time it included liaison officers from the CIA, FBI, and other nonmilitary state and federal agencies. It was headquartered at MacDill air force base in Tampa, Florida, and the ACSI and USAINTC commanders were primary leaders in developing CINCSTRIKE strategy for the mobilization of forces as required for defensive action inside CONUS.

-- Orders to Kill: The Truth Behind the Murder of Martin Luther King, by Dr. William F. Pepper

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 25153

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: ORDERS TO KILL -- THE TRUTH BEHIND THE MURDER OF MARTIN

Dr. William F. Pepper is James Earl Ray's attorney. He is a barrister in England, a U.S. Attorney and an Associate of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators. He practices international, human rights and constitutional law from London, has represented governments and heads of state, and appeared as an expert on international law issues. He has published two other books and various articles.

THE PRINCIPAL PLAYERS

The Memphis Police Department (MPD) in 1968

Frank C. Holloman former FBI agent and Director of Memphis Police and Fire Departments

J. C. MacDonald Chief of police

William O. Crumby Assistant Chief

Sam Evans Inspector-head of all Special Services including the emergency tactical units (TACT)

Don Smith Inspector in charge of Dr. King's personal security in Memphis in the 1960

N. E. Zachary Inspector-homicide

Eli H. Arkin operational head of the intelligence bureau

J. C. Davis detective in the intelligence bureau

Emmett Douglass driver of TACT 10 cruiser on afternoon of April 4, 1968

Joe B. Hodges patrolman/ dog officer

Barry Neal Linville homicide detective

Marrell McCollough undercover intelligence officer assigned to infiltrate the Invaders

Ed Redditt black detective seconded to intelligence bureau

Willie B. Richmond black intelligence bureau officer

Jim Smith officer assigned to Special Services and detailed to intelligence; later attorney general's investigator

Tommy Smith homicide detective

Jerry Williams black detective

The Memphis Fire Department in 1968

Carthel Weeden captain in charge of station 2

Lt. George Loenneke second in command station 2

William King fireman station 2

Floyd Newsom black fireman station 2

Norvell Wallace black fireman station 2

The Judges

Preston Battle, Jr. Shelby County Criminal Court trial judge in 1968

Joe Brown, Jr. Shelby County Criminal Court trial judge in 1994-95

The Prosecutors

Phil Canale Shelby County District Attorney General in 1968-69

John Pierotti Shelby County District Attorney General in 1993-95

James Earl Ray's Lawyers

Arthur Hanes Sr. & Arthur (now Judge) Hanes Jr. James Earl Ray's first lawyers

Percy Foreman James Earl Ray's second lawyer

Hugh Stanton Sr. court appointed defense co-counsel with Percy Foreman in 1968-69

James Lesar James Earl Ray's lawyer in the early 1970s

Jack Kershaw James Earl Ray's lawyer in the mid 1970s

Mark Lane James Earl Ray's lawyer from 1977 to the early 1980s

William F. Pepper (Author) chief counsel 1988 to present

Wayne Chastain Memphis attorney-defense associate counsel 1993 to present; Memphis Press Scimitar reporter in 1968

The U.S. Government

Executive Branch in 1967-68

Lyndon Baines Johnson President

Robert S. McNamara Secretary of Defense

The FBI in 1967-68

J. Edgar Hoover The director

Clyde Tolson associate director; close friend and heir of J. Edgar Hoover

Cartha DeLoach assistant Director

William C. Sullivan assistant director in charge of Domestic Intelligence Division and expansion of COINTELPRO (Counter-Intelligence Program) operations

Patrick D. Putnam special agent seconded to U.S. army Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence

Robert G. Jensen special agent in charge (SAC) Memphis field office

William Lawrence special agent in charge of intelligence for the Memphis field office

Joe Hester Memphis field office special agent in charge of coordinating the Memphis area investigation

Al Sentinella FBI special agent in the Atlanta field office who controlled SCLC informant James Harrison in 1967-68

Arthur Murtagh FBI agent assigned to the Atlanta field office in 1967-68

The CIA in 1967-68

Richard M. Helms Director

U.S. Army in 1967-68

OFFICE OF CHIEF OF STAFF

Gen. Harold Johnson Chief of Staff

ARMY INTELLIGENCE

Brigadier General William M. Blakefield Commanding officer United States Army Intelligence Command

Major General William P. Yarborough Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence ("ACSI")

Gardner (pseudonym) key aide of 902nd Military Intelligence Group

Col. F. E. van Tassell Commanding Officer, ACSI office security and Counter-Intelligence Analysis Board ("CIAB")

Gardner's aide (pseudonym) Gardner's aide-his number two

Herbert (pseudonym) staff officer ACSI's office, Pentagon

Col. Robert McBride Commanding officer 111th Military Intelligence Group, Ft. McPherson, Georgia

20TH SPECIAL FORCES GROUP (20TH SFG) IN 1967-68,

HEADQUARTERS, BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA

Co1. Henry M. Cobb, Jr. Commanding Officer

Major Bert E. Wride second in command

Capt. Billy Eidson (dec.) Alabama contingent

Second Lt. Robert Worley (dec.) Mississippi contingent

Staff Sgt. Murphy (pseudonym) Alabama contingent

Staff Sgt. Warren (pseudonym) Alabama contingent

Buck Sgt. J. D. Hill (dec.) Mississippi contingent

PSYCHOLOGICAL OPERATIONS (PSY OPS")

Reynolds (pseudonym) photographic surveillance officer

Norton (pseudonym) photographic surveillance officer

The House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA)

Louis Stokes Chairman of the HSCA

Richard Sprague former Pennsylvania prosecutor and first HSCA chief counsel in 1976

Robert Blakey chief counsel of the HSCA 1977-79

Walter Fauntroy Chairman sub-committee on the Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1976-79

Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) Officials In 1967-68 Who Were Witnesses To Significant Events Or On The Scene

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. president

Rev. Dr. Ralph D. Abemathy vice president/treasurer

Rev. Andrew Young executive vice president

Rev. Hosea Williams chief field organizer

Rev. James Orange field organizer

Rev. James Lawson Memphis representative who invited Dr. King to Memphis

The Invaders in 1967-68

Charles Cabbage

Dr. Coby Smith

"Big" John Smith

Charles "Izzy" Harrington

Calvin Taylor

Other Significant Figures

Lavaca (Whitlock) Addison owner of a restaurant frequented by Frank C. Liberto in 1978

Willie Akins friend of Loyd Jowers

Amaro ("Armando") cousin of Raul

Walter Bailey owner/manager of the Lorraine Motel in 1968

Clifton Baird Louisville, Kentucky police officer in 1965

Arthur Baldwin Memphis topless club owner in the 1970s

Myron Billet occasional driver for Chicago mob leader Sam Giancana in the 1960s

Kay Black reporter for the Memphis Press Scimitar in 1968

Ray Blanton Governor of Tennessee in 1976 when Ray escaped from prison

Earl Caldwell New York Times reporter at the Lorraine Motel on April 4, 1968

Carson (pseudonym) associate/friend of Sgt. J. D. Hill of 20th SFG

Sid Carthew British merchant seaman who visited the Neptune tavern in Montreal in 1967

Cheryl (pseudonym) acquaintance/associate of Amaro ____ and his cousin Raul ____ from 1962-1979

Joe "Zip" Chimento Marcello New Orleans associate and coordinator of Marcello weapons trading and gunrunning in 1967-68

Chuck (pseudonym) six year old boy in 1968, alledgedly sitting in parked car on Mulberry Street at the time of the shooting

Morris Davis FBI/DEA informant in 1968 and HSCA informant/researcher in 1977-78

Daniel Ellsberg former defense department specialist who released the Pentagon Papers

Hickman Ewing, Jr . former U .S. attorney and chief prosecuting counsel for the television trial of James Earl Ray

April Ferguson associate of Mark Lane in 1978 and defense co-counsel for the television trial of James Earl Ray

Marvin E. Frankel former U .S. federal District Court judge and judge for the television trial of James Earl Ray

Eric S. Galt employee in 1967-68 at Union Carbide Corporation's Toronto operation with U.S. government Top Secret security clearance; the identity used by James Earl Ray in 1967-68

Lewis Garrison Memphis attorney for Loyd Jowers

Memphis Godfather Carlos Marcello's principal associate in Memphis

James Harrison SCLC controller in 1967-68 and paid FBI informant

Ray Alvis Hendrix eyewitness who left Jim's Grill ten to fifteen minutes before the shooting on April 4, 1968

Kenneth Herman Memphis private investigator

O. D. Hester "Slim" friend of Ezell Smith

Frank Holt trucker's helper employed by M. E. Carter in 1968

Charles Hurley Memphis resident who picked up his wife in front of the rooming house on the afternoon of April 4, 1968

Solomon Jones Dr. King's driver in Memphis in 1968

Loyd Jowers owner of Jim's Grill on South Main Street in Memphis in 1968

Jim Kellum Memphis private investigator for the defense

(William) Tim Kirk inmate at Shelby County Jail 1978, and at Riverbend Maximum Security Prison in 1992-present

Reverend Samuel "Billy" Kyles Memphis minister

James Latch Vice president of Memphis LL&L Produce Company and partner of Liberto in 1968

Frank Camille Liberto President of LL&L Produce Company in Memphis in 1968

Phillip Manuel investigator for the Permanent Sub-Committee on Investigations of the United States Senate in 1968

Carlos Marcello New Orleans, mafia leader in 1967-68

John W. ("Bill") McAfee Memphis photographer covering Dr. King on assignment from network television on April 4, 1968

James McCraw Yellow Cab driver in 1968, driving on the evening of April 4

John McFerren Somerville, Tennessee businessman and civil rights leader in 1968

Sheriff Bill Morris Shelby County Sheriff in 1967-68

Red Nix Marcello organization contract killer

Oliver Patterson FBI and HSCA informant in 1977-78

Paul ____ Yellow Cab driver in 1968, driving on the evening of April 4

Raul ____ shadowy figure whom James Earl Ray met in the Neptune Bar in Montreal in July 1967

James Earl Ray the alleged assassin of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. who has as of March 10, 1995 been in prison for 26 years

Jerry Ray youngest brother of James Earl Ray

John Ray younger brother of James Earl Ray

William Zenie Reed eyewitness who left Jim's Grill ten to fifteen minutes before the shooting on April 4, 1968

Randy Rosenson man whose name was on a business card found by James Earl Ray in the Mustang in 1967

Jack Saltman Thames Television producer of the Trial of James Earl Ray in 1993

William Sartor Time magazine stringer and investigative reporter, died mysteriously in 1971

Bobbi Smith waitress at Jim's Grill in 1967-68

Ezell Smith employee at a Liberto family business in Memphis in 1968

Betty Spates mistress of Loyd Jowers in 1967-68 and waitress at Jim's Grill

Dr. Benjamin Spock pediatrician, author, political activist and potential "ice president candidate on a proposed King-Spock ticket in 1968

Gene Stanley

former U .S. Attorney and Knoxville lawyer for Randy Rosenson in the 1970s

Charles Quitman Stephens 422-1/2 South Main Street rooming house tenant in room 6-B and State's chief witness against James Earl Ray in 1968

Maynard Stiles deputy director of the Memphis Public Works department in 1968

Alexander Taylor senior Florida intelligence officer in 1968

Steve Tompkins Memphis Commercial Appeal reporter in 1993

Ross Vallone Houston associate of Carlos Marcello in 1967-68

Louie Ward Yellow Cab driver in 1968, driving on the evening of April 4

Nathan Whitlock son of Lavada (Whitlock) Addison who met Frank C. Liberto in 1978 in his mother's restaurant

John Willard alias used by James Earl Ray for renting a room at 422-1/2 South Main Street on April 4, 1968

Glenn Wright prosecution co-counsel in the television trial of James Earl Ray

Walter Alfred "Jack" Youngblood U .S. army Vietnam Special Operations Group operative, pilot, intelligence agent and mercenary

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 25153

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: ORDERS TO KILL -- THE TRUTH BEHIND THE MURDER OF MARTIN

INTRODUCTION

LIKE MOST PEOPLE, I accepted the official story about how Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was murdered. I believe this was the result of my naivete or perhaps the desire to put the loss of a friend behind me. In any case, when Dr. Benjamin Spock, the pediatrician and antiwar activist, and I traveled to Memphis for the memorial march on April 8, 1968, four days after the assassination, so far as I was concerned it was in the hands of the police.

In the following years, I heard about inconsistencies in the state's case and rumors of a conspiracy in which James Earl Ray was framed for Dr. King's murder. Then in 1977-1978, at the Rev. Ralph Abernathy's request I prepared for and then conducted a five-hour interview of James Earl Ray. Since that time, the mystery of Dr. King's assassination has dominated much of my life. In no small measure I suppose this is because of the responsibility I feel for having initially prompted him to oppose the Vietnam War -- for that stand was a major factor contributing to his death.

The intervening years have only strengthened my belief that Dr. King's assassination constituted the greatest loss suffered by the republic this century. To understand his death it is essential to realize that though he is popularly depicted and perceived as a civil rights leader, he was much more. A nonviolent revolutionary, he personified the most powerful force for long overdue social, political, and economic reconstruction of the nation.

Those in charge of the United States intelligence, military, and law enforcement machinery understood King's true significance. They perceived his active opposition to the war and is organizing of the poor as grave disruptions to the stability of a society already rife with unrest, and took the position that he was under communist control.

The last year of his life was one of the most turbulent in the history of the nation. Much of the civil unrest took the form of nationwide urban riots and was clearly the result of racial tensions, frustrations and anger at oppressive living conditions and the endemic hopelessness of inner-city life. However, one cannot consider these explosions without taking into account the pervasive presence of the war, its legitimization of violence, and its overall impact on the neighborhoods of the nation. By July 1967, the number of riots and other serious disruptions against public order had reached ninety-three in nineteen states. In August there were an additional thirty-three riots which occurred in thirty-two cities in twenty-two states.

Dr. King was at the center of it all. His unswerving opposition to the war and his commitment to bring hundreds of thousands of poor people to a Washington D.C. encampment in the spring of 1968 to focus Congress's attention on the plight of the nation's poor, turned the government's anxiety into utter panic. I believe that there was no way Dr. King was going to be allowed to lead this army of alienated poor to Washington to take up residence in the shadow of the Washington memorial.

When army intelligence officers interviewed rioters in Detroit after the July 25, 1967 riot-which left nineteen dead, eight hundred injured, and $150 million of property damage -- they were amazed to learn that the leader most respected by those violent teenagers was not Stokely Carmichael nor H. Rap Brown but Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Six weeks after the Detroit riot the National Conference for New Politics (NCNP) scheduled a national convention over the Labor Day weekend in Chicago. The gathering of 5,000 delegates from all around the country and from every walk of life was expected to support a third-party presidential ticket of Dr. King and Dr. Spock. We now know how much shock this prospect caused at the highest levels of government.

So caught up were we in the fight for social change that we didn't appreciate the strength and determination of the opposition. It has become clear to me that by 1967 a siege mentality had descended on the nation's establishment forces, including its federal law enforcement, intelligence and military branches. At the best of times, official Washington and its appendages throughout the country are highly insular and protective. In 1967-1968, with the barbarians, as they would have regarded them, gathering just outside the gates of power, any move in defense of the system and its special economic interests would have been viewed as a patriotic duty. All significant organizations committed to ending the war or fostering social or economic change were infiltrated, subjected to surveillance, and/ or subverted.

This book has been in development since 1978 and reflects a long-term effort to uncover the truth about the assassination. It does not cover the full scope of the investigation since many leads were examined and discarded and much information, however interesting, ultimately turned out to be superfluous to the central story. In 1988, I agreed to represent James Earl Ray, and by 1990 I had become convinced that the only way to end his wrongful imprisonment would be to solve the case. The investigation on which the book is based has been focused on that goal. However, for a period of nearly seven years prior to publication, I've tried in every way possible to put evidence of James's innocence before a court. Frustrated at every turn, I now turn to the court of last resort-the American people.

This story has taken twenty-seven years to unfold. This is largely the result of the creation and perpetration of a cover-up by government authorities at local, state, and national levels.

I've become convinced that, had they not met obstruction from within their own ranks, some of the honest, competent Memphis homicide detectives I've come to know over the years could have ferreted out enough evidence to warrant indicting several Memphians on charges ranging from accessory before and after the fact, to conspiracy to murder, to murder in the first degree. Among those indicted would have been some of their fellow officers. Even without official obfuscation, however, it's unlikely that these detectives could have traced the conspiracy further afield to its various well-insulated sources.

As will become increasingly clear, it was inevitable that such a local police investigation wouldn't be allowed and that each and every politically sponsored official investigation since 1968 would disinform the public and cover up the truth.

Years of investigation led to an unscripted television trial in 1993 that resulted in a not-guilty verdict. My subsequent investigation has unearthed powerful new evidence. The stories of several key witnesses, silent for twenty-seven years, are revealed for the first time. Although we will never know each and every detail behind this most heinous crime, we now have enough hard facts to overwhelmingly support James Earl Ray's innocence. The body of new evidence, if formally considered, would compel any independent grand jury-which, as of the time of this writing, we have been seeking for a year and a half-to issue indictments against perpetrators who are still alive. Even as this book goes to press we are pursuing all possible avenues through the courts to obtain justice and free James, as well as to bring to account those guilty parties whom we have identified.

Ultimately, there are many victims in this case: Dr. King; James Earl Ray; their families, and the citizens of the United States. All have been victimized by the abject failure of their democratic institutions. The assassination of Martin Luther King and its coverup extends far and wide into all levels of government and public service. Through the extensive control of information and the failure of the system of checks and balances, government has inevitably come to serve the needs of powerful special interests. As a result, the essence of democracy-government of, by, and for the people-has been terminally eroded.

Thus, what begins as a detective story ends as a tragedy of unimagined proportions: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., is dead; James Earl Ray remains in prison; many of the guilty remain free, some even revered and honored; and our faith in the United States of America is shaken to the core.

William F. Pepper

London, England

LIKE MOST PEOPLE, I accepted the official story about how Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was murdered. I believe this was the result of my naivete or perhaps the desire to put the loss of a friend behind me. In any case, when Dr. Benjamin Spock, the pediatrician and antiwar activist, and I traveled to Memphis for the memorial march on April 8, 1968, four days after the assassination, so far as I was concerned it was in the hands of the police.

In the following years, I heard about inconsistencies in the state's case and rumors of a conspiracy in which James Earl Ray was framed for Dr. King's murder. Then in 1977-1978, at the Rev. Ralph Abernathy's request I prepared for and then conducted a five-hour interview of James Earl Ray. Since that time, the mystery of Dr. King's assassination has dominated much of my life. In no small measure I suppose this is because of the responsibility I feel for having initially prompted him to oppose the Vietnam War -- for that stand was a major factor contributing to his death.

The intervening years have only strengthened my belief that Dr. King's assassination constituted the greatest loss suffered by the republic this century. To understand his death it is essential to realize that though he is popularly depicted and perceived as a civil rights leader, he was much more. A nonviolent revolutionary, he personified the most powerful force for long overdue social, political, and economic reconstruction of the nation.

Those in charge of the United States intelligence, military, and law enforcement machinery understood King's true significance. They perceived his active opposition to the war and is organizing of the poor as grave disruptions to the stability of a society already rife with unrest, and took the position that he was under communist control.

The last year of his life was one of the most turbulent in the history of the nation. Much of the civil unrest took the form of nationwide urban riots and was clearly the result of racial tensions, frustrations and anger at oppressive living conditions and the endemic hopelessness of inner-city life. However, one cannot consider these explosions without taking into account the pervasive presence of the war, its legitimization of violence, and its overall impact on the neighborhoods of the nation. By July 1967, the number of riots and other serious disruptions against public order had reached ninety-three in nineteen states. In August there were an additional thirty-three riots which occurred in thirty-two cities in twenty-two states.

Dr. King was at the center of it all. His unswerving opposition to the war and his commitment to bring hundreds of thousands of poor people to a Washington D.C. encampment in the spring of 1968 to focus Congress's attention on the plight of the nation's poor, turned the government's anxiety into utter panic. I believe that there was no way Dr. King was going to be allowed to lead this army of alienated poor to Washington to take up residence in the shadow of the Washington memorial.

When army intelligence officers interviewed rioters in Detroit after the July 25, 1967 riot-which left nineteen dead, eight hundred injured, and $150 million of property damage -- they were amazed to learn that the leader most respected by those violent teenagers was not Stokely Carmichael nor H. Rap Brown but Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Six weeks after the Detroit riot the National Conference for New Politics (NCNP) scheduled a national convention over the Labor Day weekend in Chicago. The gathering of 5,000 delegates from all around the country and from every walk of life was expected to support a third-party presidential ticket of Dr. King and Dr. Spock. We now know how much shock this prospect caused at the highest levels of government.

So caught up were we in the fight for social change that we didn't appreciate the strength and determination of the opposition. It has become clear to me that by 1967 a siege mentality had descended on the nation's establishment forces, including its federal law enforcement, intelligence and military branches. At the best of times, official Washington and its appendages throughout the country are highly insular and protective. In 1967-1968, with the barbarians, as they would have regarded them, gathering just outside the gates of power, any move in defense of the system and its special economic interests would have been viewed as a patriotic duty. All significant organizations committed to ending the war or fostering social or economic change were infiltrated, subjected to surveillance, and/ or subverted.

This book has been in development since 1978 and reflects a long-term effort to uncover the truth about the assassination. It does not cover the full scope of the investigation since many leads were examined and discarded and much information, however interesting, ultimately turned out to be superfluous to the central story. In 1988, I agreed to represent James Earl Ray, and by 1990 I had become convinced that the only way to end his wrongful imprisonment would be to solve the case. The investigation on which the book is based has been focused on that goal. However, for a period of nearly seven years prior to publication, I've tried in every way possible to put evidence of James's innocence before a court. Frustrated at every turn, I now turn to the court of last resort-the American people.

This story has taken twenty-seven years to unfold. This is largely the result of the creation and perpetration of a cover-up by government authorities at local, state, and national levels.

I've become convinced that, had they not met obstruction from within their own ranks, some of the honest, competent Memphis homicide detectives I've come to know over the years could have ferreted out enough evidence to warrant indicting several Memphians on charges ranging from accessory before and after the fact, to conspiracy to murder, to murder in the first degree. Among those indicted would have been some of their fellow officers. Even without official obfuscation, however, it's unlikely that these detectives could have traced the conspiracy further afield to its various well-insulated sources.

As will become increasingly clear, it was inevitable that such a local police investigation wouldn't be allowed and that each and every politically sponsored official investigation since 1968 would disinform the public and cover up the truth.

Years of investigation led to an unscripted television trial in 1993 that resulted in a not-guilty verdict. My subsequent investigation has unearthed powerful new evidence. The stories of several key witnesses, silent for twenty-seven years, are revealed for the first time. Although we will never know each and every detail behind this most heinous crime, we now have enough hard facts to overwhelmingly support James Earl Ray's innocence. The body of new evidence, if formally considered, would compel any independent grand jury-which, as of the time of this writing, we have been seeking for a year and a half-to issue indictments against perpetrators who are still alive. Even as this book goes to press we are pursuing all possible avenues through the courts to obtain justice and free James, as well as to bring to account those guilty parties whom we have identified.

Ultimately, there are many victims in this case: Dr. King; James Earl Ray; their families, and the citizens of the United States. All have been victimized by the abject failure of their democratic institutions. The assassination of Martin Luther King and its coverup extends far and wide into all levels of government and public service. Through the extensive control of information and the failure of the system of checks and balances, government has inevitably come to serve the needs of powerful special interests. As a result, the essence of democracy-government of, by, and for the people-has been terminally eroded.

Thus, what begins as a detective story ends as a tragedy of unimagined proportions: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., is dead; James Earl Ray remains in prison; many of the guilty remain free, some even revered and honored; and our faith in the United States of America is shaken to the core.

William F. Pepper

London, England

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 25153

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: ORDERS TO KILL -- THE TRUTH BEHIND THE MURDER OF MARTIN

GLOSSARY

ACLU American Civil Liberties Union

ACSI Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence

agency Central Intelligence Agency

Alpha 184 Team Operation Detachment Alpha 184 Team. Special Forces Field Training Team in specialized civilian disguise selected from 20th SFG

AFSCME Association of Federal, State, County and Municipal

Employees Union

agent provocateur covert operative used to infiltrate a targeted group and influence its activity

AUTOVON first generation fax machine-state of the art in 1967

ASA Army Security Agency

asset government independent contract agent whose actions may be officially denied

behind the fence operation covert, officially deniable operations

body mass assassin's human target area-the chest area

BOP Black Organizing Project (companion organization of the Invaders)

bureau Federal Bureau of Investigation

center mass another term for "body mass" (see above)

CIA Central Intelligence Agency

CIAB Counterintelligence Analysis Board

CINCSTRIKE Commander-in-Chief U.S. Strike Command

C.O. Commanding Officer

COINTELPRO-FBI counterintelligence program aimed at targeted dissenting/protest groups.

COME Community on the Move for Equality (coalition of labor and civil rights groups in Memphis formed at the time of the sanitation workers strike spearheaded by an interracial committee organized by local clergy)

COMINFIL FBI designation for a communist infiltration investigation of a targeted group

committee House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations

CONUS Continental United States

D.A. District Attorney

DEA Drug Enforcement Agency

DEFCON Acronym for national security emergency with seriousness expressed in ascending order, e.g. DEFCON 2, 3, 4

DIA Defense Intelligence Agency

ELINT electronic intelligence surveillance

FBI Federal Bureau of Investigation

HSCA House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations

HUMINT Human Intelligence Source (informer)

IEOC Intelligence Emergency Operation Center-army intelligence communications and deployment centre which was established in an area where civil unrest was anticipated

Invaders small militant black organizing group in Memphis, oriented toward self-help

IRR Investigative Records Repository-army intelligence records repository at Fort Holabird where intelligence files on civilians were kept

LAWS light anti-tank weapon rockets

LL&L Liberto, Liberto & Latch (produce company owned by Frank C. Liberto )

MIGs Military Intelligence Groups (counterintelligence)

MPD Memphis Police Department

NAACP National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

NAS Millington Naval Air Station

NCNP National Conference for New Politics

NLF National Liberation Front

NSA National Security Agency

ONI Office of Naval Intelligence

Operation CHAOS CIA program for the collection of information on citizens and groups through the interception and reading of mail, and the placement of informants and covert operators in dissenting organizations

Operation MINARET NSA watch-list program collecting information on individuals and organizations involved in civil disturbances, antiwar movements and military deserters

OS Office of Security-department in CIA from which a variety of super secret covert operations was mounted, often involving members of organized crime

Project MERRIMAC CIA SOG project which focused on infiltration of and spying on ten major peace and civil rights groups

Project RESISTANCE 1967 OS project designed to infiltrate meetings of antiwar protestors, recruit informants and report on black student activities in cooperation with local police

Psy Ops Psychological Operations

recon. reconnaissance

SAC FBI Special Agent in Charge-ranking officer in any field office

SCLC Southern Christian Leadership Conference

SFG Special Forces Group a.k.a. the Green Berets

SNCC Student Non Violent Coordinating Committee

SOG Special Operations Group-small covert often interservice operations groups formed for a particular purpose

TACT (TAC) emergency tactical units deployed in Memphis at the time of the sanitation workers strike which consisted of twelve men in three or four vehicles

TBI Tennessee Bureau of Investigation

USAINTC U .S. Army Intelligence Command (the overall army intelligence organization)

USIB United States Intelligence Board

ACLU American Civil Liberties Union

ACSI Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence

agency Central Intelligence Agency

Alpha 184 Team Operation Detachment Alpha 184 Team. Special Forces Field Training Team in specialized civilian disguise selected from 20th SFG

AFSCME Association of Federal, State, County and Municipal

Employees Union

agent provocateur covert operative used to infiltrate a targeted group and influence its activity

AUTOVON first generation fax machine-state of the art in 1967

ASA Army Security Agency

asset government independent contract agent whose actions may be officially denied

behind the fence operation covert, officially deniable operations

body mass assassin's human target area-the chest area

BOP Black Organizing Project (companion organization of the Invaders)

bureau Federal Bureau of Investigation

center mass another term for "body mass" (see above)

CIA Central Intelligence Agency

CIAB Counterintelligence Analysis Board

CINCSTRIKE Commander-in-Chief U.S. Strike Command

C.O. Commanding Officer

COINTELPRO-FBI counterintelligence program aimed at targeted dissenting/protest groups.

COME Community on the Move for Equality (coalition of labor and civil rights groups in Memphis formed at the time of the sanitation workers strike spearheaded by an interracial committee organized by local clergy)

COMINFIL FBI designation for a communist infiltration investigation of a targeted group

committee House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations

CONUS Continental United States

D.A. District Attorney

DEA Drug Enforcement Agency

DEFCON Acronym for national security emergency with seriousness expressed in ascending order, e.g. DEFCON 2, 3, 4

DIA Defense Intelligence Agency

ELINT electronic intelligence surveillance

FBI Federal Bureau of Investigation

HSCA House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations

HUMINT Human Intelligence Source (informer)

IEOC Intelligence Emergency Operation Center-army intelligence communications and deployment centre which was established in an area where civil unrest was anticipated

Invaders small militant black organizing group in Memphis, oriented toward self-help

IRR Investigative Records Repository-army intelligence records repository at Fort Holabird where intelligence files on civilians were kept

LAWS light anti-tank weapon rockets

LL&L Liberto, Liberto & Latch (produce company owned by Frank C. Liberto )

MIGs Military Intelligence Groups (counterintelligence)

MPD Memphis Police Department

NAACP National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

NAS Millington Naval Air Station

NCNP National Conference for New Politics

NLF National Liberation Front

NSA National Security Agency

ONI Office of Naval Intelligence

Operation CHAOS CIA program for the collection of information on citizens and groups through the interception and reading of mail, and the placement of informants and covert operators in dissenting organizations

Operation MINARET NSA watch-list program collecting information on individuals and organizations involved in civil disturbances, antiwar movements and military deserters

OS Office of Security-department in CIA from which a variety of super secret covert operations was mounted, often involving members of organized crime

Project MERRIMAC CIA SOG project which focused on infiltration of and spying on ten major peace and civil rights groups

Project RESISTANCE 1967 OS project designed to infiltrate meetings of antiwar protestors, recruit informants and report on black student activities in cooperation with local police

Psy Ops Psychological Operations

recon. reconnaissance

SAC FBI Special Agent in Charge-ranking officer in any field office

SCLC Southern Christian Leadership Conference

SFG Special Forces Group a.k.a. the Green Berets

SNCC Student Non Violent Coordinating Committee

SOG Special Operations Group-small covert often interservice operations groups formed for a particular purpose

TACT (TAC) emergency tactical units deployed in Memphis at the time of the sanitation workers strike which consisted of twelve men in three or four vehicles

TBI Tennessee Bureau of Investigation

USAINTC U .S. Army Intelligence Command (the overall army intelligence organization)

USIB United States Intelligence Board

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 25153

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: ORDERS TO KILL -- THE TRUTH BEHIND THE MURDER OF MARTIN

PART 1: BACKGROUND TO THE ASSASSINATION

Chapter 1: Vietnam: Spring 1966-Summer 1967

THIS STORY BEGINS IN VIETNAM, where I had gone as a freelance journalist in the spring of 1966.

Soon the picture became clear. Wherever I went in South Vietnam, from the southern delta to the northern boundary (I corps), U.S. carpet bombing systematically devastated the ancient, village-based rural culture, slaughtering helpless peasants. Time and again, in hospitals and refugee camps, children, barely human in appearance, their flesh having been carved into grotesque forms by napalm, described the "fire bombs" that rained from the sky onto their hamlets.

After a time in the field, I suffered a minor injury in a crash landing near Pleiku caused by ground fire. I returned to Saigon, where I went to a party held by some casual friends. I was tired and upset. For several days in the Central Highlands I had been confronted with one atrocity after another. Because I was far from a battle-hardened correspondent, I wasn't taking it very well. Soon I was approached by a young Vietnamese woman who solicited information from me. Aided by a few drinks, I expressed my disgust with the U.S. involvement in the war. The woman appeared sympathetic. After that evening, I never saw her again.

The next day I was summoned by Navy Commander Madison, the press accrediting officer, who my colleagues advised was an intelligence operative. He commented on my absence from the daily Saigon press briefings (at which the military line was disseminated) and stated that he had received reports of unacceptable remarks made by me. He advised me that my accreditation was going to be revoked.

I returned home and began to prepare articles for publication and testimony to be given before Sen. Edward M. Kennedy's Subcommittee to Investigate Problems Connected with Refugees and Escapees. My article "The Children of Vietnam" was published by Ramparts in January! 1967, during which time Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was becoming increasingly concerned over the Johnson administration. s plans to reduce its domestic antipoverty spending in order to channel more funds to the war effort.

Dr. King hadn't yet categorically broken with the White House over the issue, but soon after the Ramparts article appeared he received calls from Yale chaplain William Sloane Coffin, Nation editor Carey McWilliams, Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas, and others, urging him to take a more forceful antiwar stand and, indeed, to even consider running as a third-party presidential candidate in 1968. I would later learn that wiretaps of the conversations in which the candidacy was discussed were relayed to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and, through him, to Lyndon Johnson.

On Saturday, January 14, King flew to Jamaica, where he had planned to work on a book about one of his most ardently held beliefs -- the idea of a guaranteed income for each adult citizen. He was accompanied by his friend and associate Bernard Lee. While having breakfast he began to read the January Ramparts. According to Lee, and also recorded by David Garrow in his historical account, Bearing the Cross [1] Dr. King was galvanized by my account of atrocities against civilians and the accompanying photographs. Although he had spoken out against the war before, he decided then and there to do everything in his power to stop it.

Dr. King's new commitment to oppose the war became his priority. He told black trade unionist Cleveland Robinson and longtime advisor Stanley Levison that he was prepared to break with the Johnson administration regardless of the financial consequences and even the personal peril. [2] He saw, as never before, the necessity of tying together the peace and civil rights movements, and soon became involved in the antiwar effort. He spoke at a forum sponsored by the Nation in Los Angeles on February 25, 1967, joined Benjamin Spock (a proposed running mate in his possible third-party candidacy) in his first anti-war march, through downtown Chicago on March 23, and began to prepare for a major address on the war to be presented at the April 15 Spring Mobilization demonstration in New York.

From the beginning of the year, he began to devote more time to the development of a new coalition. He had come to believe it was time to unite the various progressive, single-issue organizations to form a mighty force, whose power would come from increased numbers and pooled funds. The groups all opposed the war and all wanted equal rights for blacks and other minorities, but their primary concern was eliminating poverty in the wealthiest nation on earth. These common issues formed the basis of the "new politics," and the National Conference for New Politics (NCNP) was established to catalyze a nation- wide effort. I was asked to be its executive director.

Though our emphasis was on grassroots political organizing, our disgust with the "old politics," particularly as practiced by the Johnson administration, compelled the NCNP to consider developing an independent presidential candidacy. To decide on this and adopt a platform, a national convention -- to be attended by delegates from every organization for social change across the land-was scheduled for the 1967 Labor Day weekend at the Palmer House in Chicago.

In New York on Tuesday, April 4, exactly twelve months be fore his death, Dr. King addressed an audience of more than three thousand at Riverside Church and made his formal declaration of opposition to the war. He expressed his concern that his homeland, the Great Republic of old, would never again be seen to reflect for the world "the image of revolution, freedom and democracy, but rather come to mirror the image of violence and militarism." He called for conscientious objection, antiwar demonstrations, political activity, and a revolution of values whereby American society would radically shift from materialism to humanism.

Response to the speech was prompt and overwhelmingly condemnatory. Old friends (such as Phil Randolph and Bayard Rustin) either refused to comment publicly or disassociated themselves from King's position. The domestic economic and civil rights progress of Lyndon Johnson was strongly supported by liberals and civil rights leaders who were loathe to alienate the president by opposing his war effort. I noted Dr. King's increasing pessimism that resulted from continued sniping from civil rights leaders like Roy Wilkins of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and Whitney Young of the National Urban League. (We didn't know at the time that Wilkins was meeting and working with the FBI's assistant director, Cartha DeLoach, [3] throughout this period.) Even some of King's closest longstanding personal advisors were opposed to the speech. For example, it was ironic that Stanley Levison, long labeled by the FBI as the strongest "communist" influence on Dr. King, attempted in every way possible to restrain. King's efforts to oppose the war formally.

The reaction from newspaper editorials was virtually always negative. The Washington Post, the New York Times, and Life magazine joined the chorus of criticism.

During the run up to the April 15 antiwar demonstration, Dr. King and I discussed not only the effect of the U.S. war effort in Vietnam but also political strategy in general and particular details of the demonstration. Five days before the demonstration, the NAACP board of directors passed a resolution attacking King's effort to link the peace and civil rights movements. Martin said to me in a moment of frustration, "They're all going to turn against me now, but still we must press on. You and the others must not only be steadfast, but constantly so."

He and others asked me to put forward the idea of a King-Spock ticket at the demonstration. He didn't want to appear to be explicitly seeking such a nomination, for the media would certainly paint him as engaging in a self- serving quest, to the detriment of his professed calling and cause. If, on the other hand, he was pressed or drafted into the race, he could answer the call and run-not to win, but to heighten national debate and awareness.

On April 15, as Dr. King concluded his speech by calling on the government to "stop the bombing," the crowd had grown to about 250,000 cheering and chanting partisans. When I put forward the notion of a King-Spock ticket, the assembled mass exploded as one in support. For many of us the end of that demonstration marked the first step in the establishment of a "new politics" in the United States.

On April 23, 1967, as Martin and I rode together to Massachusetts to announce, with Ben Spock, the beginning of a grassroots organizing project called Vietnam Summer, a man whose name meant nothing to us at the time but whose life was to become inextricably intertwined with ours, was being helped into a bread box in the kitchen of the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City. The box was loaded onto a delivery truck that would take James Earl Ray through the gates to freedom.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 25153

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: ORDERS TO KILL -- THE TRUTH BEHIND THE MURDER OF MARTIN

Chapter 2: Death of the New Politics: Summer 1967-Spring 1968

THE NCNP CONVENTION ON LABOR DAY WEEKEND 1967 began with great enthusiasm and expectation. Many of us believed that nothing less than the nation's rebirth was on the agenda. Dr. King's rousing keynote address, calling for unity and action, brought forth an overwhelming response from the 5,000 delegates. It was the most political speech he would ever give.

There was, however, an ominous presence. A small aggressive group had pressed each arriving black delegate into a self-styled Black Caucus. Dr. King's safety was in danger from this group, which had threatened to take him hostage, so he had to depart quickly under guard as soon as he finished speaking.

Torn by dissension, the convention descended into a fiasco; any chance of achieving a unified political movement was destroyed.

More than a decade would pass before we would become aware of the extent of the government's role in the disaster. And not until later than that would we realize that a coalition of private and public forces had orchestrated it.

For example, we would learn that a CIA operation, named Operation CHAOS, had been put in place to enable the subversion of dissent and undermine such gatherings of dissenting citizens. Operation CHAOS involved the collection of information on private citizens and groups through the interception and reading of mail, and the placement of informants and covert operators in dissenting organizations. At the NCNP convention, the tactic used was to divide the black and white delegates using the so-called Black Caucus, which we thought at the time was a natural outgrowth of the legitimate Black Power movement.

Black Caucus delegates voted en bloc and used outrageous techniques-provoking strident emotionalism; playing on white guilt, divisiveness, and intimidation; calling for the use of arms; and introducing blatantly anti-Semitic resolutions. Years later we learned that they were organized by the government and backed by federal funds, filtered through Chicago Mayor Richard Daley's antipoverty organization, and that the members included individuals from one of Chicago's most feared street gangs-the Blackstone Rangers.

The convention became hopelessly embroiled in animosity and walkouts by some leading liberal sponsors of the New Politics movement itself. Some, like Martin Peretz (the Harvard instructor, who was one of the moving forces) felt personally betrayed, understandably so considering the amount of time and resources they had expended on the convention. We didn't admit it at the time, but the NCNP died as a political force that weekend. Its focus permanently changed from national political activity to fragmented local political organizing efforts.

The inevitable weakening of these disparate efforts made them easy marks for infiltration by groups of agents provocateurs. (One such organization, the Invaders, would emerge in Memphis. This group of twenty or so black men and women developed a series of programs designed to address local needs by providing services where none had previously existed. The Invaders were significant because of their proximity to Dr. King in the weeks leading up to his assassination. They were infiltrated by intelligence operatives and subjected to surveillance out of all proportion to any threat they might have posed to the Memphis power structure.)

***

DR. KING AND I KEPT IN TOUCH AFTER THE CONVENTION. Though he was immensely disappointed by the Chicago catastrophe, he nevertheless increased his antiwar efforts. He also threw himself into the development of the Poor People's Campaign, scheduled to assemble in Washington in the late spring of 1968. The first phase of this campaign would bring to Washington up to several hundred thousand blacks, Hispanics, American Indians, poor whites, and compatriot students and intellectuals from allover the country. A tent city would be set up and civil disobedience tactics would be taught and used, if necessary, to get the attention of the White House, Congress, and various government agencies.

This combination of opposition to the war and a call for redistribution of the nation's wealth served to increase King's unpopularity with the government. It also antagonized segments of the black and white middle class as well as the black church. No doubt it confirmed the belief held by certain public and private forces that King was a serious threat to the very order and system of U.S. government. No one could predict what would happen when he led a massive wave of alienated citizens to take up residence in the nation's capital.

Those close to Dr. King noticed how the pace of his radicalization increased in the last year of his life. His analysis of the problems of American society had become much broader. His growing belief in the necessity of dissent against powerful special interests was, in fact, much like Jefferson's assertion that ultimate power should always flow from the people, otherwise tyranny results.

This perspective was driven home to me in the course of our last meeting. The last time I saw him alive was in Dean John Bennett's study at Union Theological Seminary in New York City. It was March 1968, and Andrew Young, executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and Ben Spock were also present. Spock was seeking Martin's active support for draft resistance, since Martin believed that the war was tantamount to genocide by conscription. At this time Martin was becoming fully involved in a strike of sanitation workers in Memphis. He spoke about the necessity of empowering such urban blacks through nonviolent action.

THE NCNP CONVENTION ON LABOR DAY WEEKEND 1967 began with great enthusiasm and expectation. Many of us believed that nothing less than the nation's rebirth was on the agenda. Dr. King's rousing keynote address, calling for unity and action, brought forth an overwhelming response from the 5,000 delegates. It was the most political speech he would ever give.

There was, however, an ominous presence. A small aggressive group had pressed each arriving black delegate into a self-styled Black Caucus. Dr. King's safety was in danger from this group, which had threatened to take him hostage, so he had to depart quickly under guard as soon as he finished speaking.

Torn by dissension, the convention descended into a fiasco; any chance of achieving a unified political movement was destroyed.

More than a decade would pass before we would become aware of the extent of the government's role in the disaster. And not until later than that would we realize that a coalition of private and public forces had orchestrated it.

For example, we would learn that a CIA operation, named Operation CHAOS, had been put in place to enable the subversion of dissent and undermine such gatherings of dissenting citizens. Operation CHAOS involved the collection of information on private citizens and groups through the interception and reading of mail, and the placement of informants and covert operators in dissenting organizations. At the NCNP convention, the tactic used was to divide the black and white delegates using the so-called Black Caucus, which we thought at the time was a natural outgrowth of the legitimate Black Power movement.

Black Caucus delegates voted en bloc and used outrageous techniques-provoking strident emotionalism; playing on white guilt, divisiveness, and intimidation; calling for the use of arms; and introducing blatantly anti-Semitic resolutions. Years later we learned that they were organized by the government and backed by federal funds, filtered through Chicago Mayor Richard Daley's antipoverty organization, and that the members included individuals from one of Chicago's most feared street gangs-the Blackstone Rangers.

The convention became hopelessly embroiled in animosity and walkouts by some leading liberal sponsors of the New Politics movement itself. Some, like Martin Peretz (the Harvard instructor, who was one of the moving forces) felt personally betrayed, understandably so considering the amount of time and resources they had expended on the convention. We didn't admit it at the time, but the NCNP died as a political force that weekend. Its focus permanently changed from national political activity to fragmented local political organizing efforts.

The inevitable weakening of these disparate efforts made them easy marks for infiltration by groups of agents provocateurs. (One such organization, the Invaders, would emerge in Memphis. This group of twenty or so black men and women developed a series of programs designed to address local needs by providing services where none had previously existed. The Invaders were significant because of their proximity to Dr. King in the weeks leading up to his assassination. They were infiltrated by intelligence operatives and subjected to surveillance out of all proportion to any threat they might have posed to the Memphis power structure.)

***

DR. KING AND I KEPT IN TOUCH AFTER THE CONVENTION. Though he was immensely disappointed by the Chicago catastrophe, he nevertheless increased his antiwar efforts. He also threw himself into the development of the Poor People's Campaign, scheduled to assemble in Washington in the late spring of 1968. The first phase of this campaign would bring to Washington up to several hundred thousand blacks, Hispanics, American Indians, poor whites, and compatriot students and intellectuals from allover the country. A tent city would be set up and civil disobedience tactics would be taught and used, if necessary, to get the attention of the White House, Congress, and various government agencies.

This combination of opposition to the war and a call for redistribution of the nation's wealth served to increase King's unpopularity with the government. It also antagonized segments of the black and white middle class as well as the black church. No doubt it confirmed the belief held by certain public and private forces that King was a serious threat to the very order and system of U.S. government. No one could predict what would happen when he led a massive wave of alienated citizens to take up residence in the nation's capital.

Those close to Dr. King noticed how the pace of his radicalization increased in the last year of his life. His analysis of the problems of American society had become much broader. His growing belief in the necessity of dissent against powerful special interests was, in fact, much like Jefferson's assertion that ultimate power should always flow from the people, otherwise tyranny results.

This perspective was driven home to me in the course of our last meeting. The last time I saw him alive was in Dean John Bennett's study at Union Theological Seminary in New York City. It was March 1968, and Andrew Young, executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and Ben Spock were also present. Spock was seeking Martin's active support for draft resistance, since Martin believed that the war was tantamount to genocide by conscription. At this time Martin was becoming fully involved in a strike of sanitation workers in Memphis. He spoke about the necessity of empowering such urban blacks through nonviolent action.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 25153

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: ORDERS TO KILL -- THE TRUTH BEHIND THE MURDER OF MARTIN

Chapter 3: Memphis: The Sanitation Workers Strike: February 1968-March 1968

Beginning in February 1968, Dr. King had received regular reports from his friend, Memphis clergyman James Lawson, pastor of Centenary Methodist Church, about the sanitation workers' dispute in that city. Ninety percent of the thirteen hundred sanitation workers in Memphis were black. They had no organization, union or otherwise, to defend their interests and no effective means to air grievances or to seek redress. However, to most of the citizens of Memphis, black and white, a strike against the city was nothing less than rebellion.

In a bitter and frustrating setback for the black community, Henry Loeb, who had been the mayor from 1960 to 1963, defeated incumbent William Ingram, who was regarded as friendly to black Memphians, in the mayoral election. Considering the new mayor's history and reputation, there was no reason for black workers to hope that their working conditions or salaries might improve.

The grievances were many. Salaries were at rock bottom, with no chance of increase. Men were often sent home arbitrarily, losing pay. Much of the equipment was antiquated and poorly maintained. In early 1968 two workers, thirty-five-year-old Echole Cole and twenty-nine-year-old Robert Walker, were literally swallowed up by a malfunctioning "garbage packer" truck. These trucks were over ten years old and in the process of being phased out. There was no workmen's compensation and neither man had life insurance. The city gave each of the families a month's pay and $500 toward funeral expenses. Mayor Loeb said that this was a moral but not a legal necessity. After the deaths of Cole and Walker, talk of a strike was widespread.

Maynard Stiles, who was second-in-command at the Memphis Public Works Department, told me, years after the event, that T. O. Jones, the head of the local union, called him the night before the strike with what Stiles regarded as a very reasonable list of demands. Stiles said that Jones wanted him to go along to the union meeting scheduled for that night and announce the city's agreement with the terms. An elated Stiles called Loeb to advise him that a settlement was at hand on very reasonable terms. Loeb ordered him not to dignify any such meeting with his presence and insisted that no terms be accepted under any circumstances. The union meeting went ahead that evening without Stiles. The next day the strike was on.

The national office of the Association of Federal, State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) sent in professional staff to handle the negotiations, which the mayor insisted on conducting in public, giving neither side any opportunity to change position. With no solution in sight, an interdenominational group of clergy intervened but made no progress.

The deadlock led to a protest march on February 23, which got out of control in the face of heavy police provocation. Ultimately, the police used Mace on men, women, and children-marchers and bystanders alike. Afterward, a strike strategy committee was formed with the Rev. James Lawson as its chairman. Rev. Lawson had been one of the founders of the SCLC and had worked with the organization for a decade. Dr. King regarded him highly.

Meanwhile, Dr. King was closing a leadership conference in Miami. While knowing that most of his audience disagreed with the Poor People's Campaign, he insisted that the nation had to be awakened to the issues of poverty and hunger. The shantytown he planned to erect in Washington would ensure that the plight of the American poor would be foremost in the consciousness of the people of the nation, even the world.

"We are Christian ministers and ... we are God's sanitation workers, working to clear up the snow of despair and poverty and hatred. ..." he told them.

In Memphis, a city injunction against the strike intensified the black community's support for the sanitation workers, and consumer boycotts and daily marches through the downtown area were organized. The director of the Memphis police and fire departments, Frank Holloman, who had agreed that he would allow the marches if they were peaceful, withdrew many of the visible, uniformed police. Holloman had been a special agent of the FBI for twenty-five years. For seven of those years (1952-1959), he had been in charge of director J. Edgar Hoover's Washington office. In Memphis he had no support from the black leaders. Internally he relied heavily on his chief, J. C. MacDonald (who in 1968 was close to retirement), a group of seven assistant chiefs, Inspector Sam Evans who was in charge of all Special Services, and Lieutenant Eli H. Arkin of the police department's intelligence bureau.

***

The growing involvement of young blacks, particularly high school students who were being organized by the Invaders and their parallel organization, the Black Organizing Project (BOP), brought an increased volatility to the strike. During a boycott of local merchants, these young people harassed blacks who made purchases in downtown stores. The militants made themselves heard throughout the dispute, and various Invaders were arrested for disorderly conduct, for trying to persuade students to leave school, and for blocking traffic. In retrospect, the Invaders' actions seem mild in comparison with those of other black power groups in other parts of the country.

Community on the Move for Equality (COME), a coalition of labor and civil rights groups spearheaded by an Internal Committee of local clergy, which was now running the strike, sought national as well as local publicity, scheduling nationally prominent leaders to speak in Memphis in support of the workers. The local NAACP chapter asked Roy Wilkins to come; the local union sought to bring in longtime civil rights leader Bayard Rustin; and the Rev. Lawson raised the possibility of bringing Dr. King to Memphis. Wilkins and Rustin finally agreed to come on March 14.

Lawson, who had been keeping Dr. King abreast of developments, approached him in late February when the civil rights leader was close to physical exhaustion. It was around this time that his doctor had ordered complete rest.

***

At first King had been reluctant to become directly involved. He had delivered speeches in Memphis but had never headed any civil rights activity there aside from leading the so-called "march against fear," which was organized in response to the Mississippi shooting of James Meredith, the first black to enroll at the University of Mississippi. But even though some SCLC executive staff wanted to stay away from the strike, Dr. King came to see it as being directly relevant to the national campaign.

What group could be more illustrative of the exploitation he sought to dramatize than these lowliest nonunion workers who daily took the garbage away from the city's homes? King's involvement was potentially a high-profile activity (though with some risks) that would lead naturally into the Washington Poor People's Campaign. Because Memphis contained a small, militant, black organizing group (the Invaders) as well as the more conservative, southern black congregations, it was, in his view, a microcosm of the nation, with all of the attendant problems and obstacles to the development of a successful coalition. How could he turn his back on the real, current struggle of the Memphis sanitation workers?

In early March the Rev. Lawson made the announcement that the city had been waiting for. The SCLC had transferred a March 18 staff meeting scheduled for Clarksdale, Mississippi, to Memphis, and on that evening Dr. King would address a gathering of strike supporters.

Beginning in February 1968, Dr. King had received regular reports from his friend, Memphis clergyman James Lawson, pastor of Centenary Methodist Church, about the sanitation workers' dispute in that city. Ninety percent of the thirteen hundred sanitation workers in Memphis were black. They had no organization, union or otherwise, to defend their interests and no effective means to air grievances or to seek redress. However, to most of the citizens of Memphis, black and white, a strike against the city was nothing less than rebellion.

In a bitter and frustrating setback for the black community, Henry Loeb, who had been the mayor from 1960 to 1963, defeated incumbent William Ingram, who was regarded as friendly to black Memphians, in the mayoral election. Considering the new mayor's history and reputation, there was no reason for black workers to hope that their working conditions or salaries might improve.

The grievances were many. Salaries were at rock bottom, with no chance of increase. Men were often sent home arbitrarily, losing pay. Much of the equipment was antiquated and poorly maintained. In early 1968 two workers, thirty-five-year-old Echole Cole and twenty-nine-year-old Robert Walker, were literally swallowed up by a malfunctioning "garbage packer" truck. These trucks were over ten years old and in the process of being phased out. There was no workmen's compensation and neither man had life insurance. The city gave each of the families a month's pay and $500 toward funeral expenses. Mayor Loeb said that this was a moral but not a legal necessity. After the deaths of Cole and Walker, talk of a strike was widespread.

Maynard Stiles, who was second-in-command at the Memphis Public Works Department, told me, years after the event, that T. O. Jones, the head of the local union, called him the night before the strike with what Stiles regarded as a very reasonable list of demands. Stiles said that Jones wanted him to go along to the union meeting scheduled for that night and announce the city's agreement with the terms. An elated Stiles called Loeb to advise him that a settlement was at hand on very reasonable terms. Loeb ordered him not to dignify any such meeting with his presence and insisted that no terms be accepted under any circumstances. The union meeting went ahead that evening without Stiles. The next day the strike was on.

The national office of the Association of Federal, State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) sent in professional staff to handle the negotiations, which the mayor insisted on conducting in public, giving neither side any opportunity to change position. With no solution in sight, an interdenominational group of clergy intervened but made no progress.

The deadlock led to a protest march on February 23, which got out of control in the face of heavy police provocation. Ultimately, the police used Mace on men, women, and children-marchers and bystanders alike. Afterward, a strike strategy committee was formed with the Rev. James Lawson as its chairman. Rev. Lawson had been one of the founders of the SCLC and had worked with the organization for a decade. Dr. King regarded him highly.

Meanwhile, Dr. King was closing a leadership conference in Miami. While knowing that most of his audience disagreed with the Poor People's Campaign, he insisted that the nation had to be awakened to the issues of poverty and hunger. The shantytown he planned to erect in Washington would ensure that the plight of the American poor would be foremost in the consciousness of the people of the nation, even the world.

"We are Christian ministers and ... we are God's sanitation workers, working to clear up the snow of despair and poverty and hatred. ..." he told them.

In Memphis, a city injunction against the strike intensified the black community's support for the sanitation workers, and consumer boycotts and daily marches through the downtown area were organized. The director of the Memphis police and fire departments, Frank Holloman, who had agreed that he would allow the marches if they were peaceful, withdrew many of the visible, uniformed police. Holloman had been a special agent of the FBI for twenty-five years. For seven of those years (1952-1959), he had been in charge of director J. Edgar Hoover's Washington office. In Memphis he had no support from the black leaders. Internally he relied heavily on his chief, J. C. MacDonald (who in 1968 was close to retirement), a group of seven assistant chiefs, Inspector Sam Evans who was in charge of all Special Services, and Lieutenant Eli H. Arkin of the police department's intelligence bureau.

***

The growing involvement of young blacks, particularly high school students who were being organized by the Invaders and their parallel organization, the Black Organizing Project (BOP), brought an increased volatility to the strike. During a boycott of local merchants, these young people harassed blacks who made purchases in downtown stores. The militants made themselves heard throughout the dispute, and various Invaders were arrested for disorderly conduct, for trying to persuade students to leave school, and for blocking traffic. In retrospect, the Invaders' actions seem mild in comparison with those of other black power groups in other parts of the country.

Community on the Move for Equality (COME), a coalition of labor and civil rights groups spearheaded by an Internal Committee of local clergy, which was now running the strike, sought national as well as local publicity, scheduling nationally prominent leaders to speak in Memphis in support of the workers. The local NAACP chapter asked Roy Wilkins to come; the local union sought to bring in longtime civil rights leader Bayard Rustin; and the Rev. Lawson raised the possibility of bringing Dr. King to Memphis. Wilkins and Rustin finally agreed to come on March 14.

Lawson, who had been keeping Dr. King abreast of developments, approached him in late February when the civil rights leader was close to physical exhaustion. It was around this time that his doctor had ordered complete rest.

***

At first King had been reluctant to become directly involved. He had delivered speeches in Memphis but had never headed any civil rights activity there aside from leading the so-called "march against fear," which was organized in response to the Mississippi shooting of James Meredith, the first black to enroll at the University of Mississippi. But even though some SCLC executive staff wanted to stay away from the strike, Dr. King came to see it as being directly relevant to the national campaign.

What group could be more illustrative of the exploitation he sought to dramatize than these lowliest nonunion workers who daily took the garbage away from the city's homes? King's involvement was potentially a high-profile activity (though with some risks) that would lead naturally into the Washington Poor People's Campaign. Because Memphis contained a small, militant, black organizing group (the Invaders) as well as the more conservative, southern black congregations, it was, in his view, a microcosm of the nation, with all of the attendant problems and obstacles to the development of a successful coalition. How could he turn his back on the real, current struggle of the Memphis sanitation workers?

In early March the Rev. Lawson made the announcement that the city had been waiting for. The SCLC had transferred a March 18 staff meeting scheduled for Clarksdale, Mississippi, to Memphis, and on that evening Dr. King would address a gathering of strike supporters.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 25153

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: ORDERS TO KILL -- THE TRUTH BEHIND THE MURDER OF MARTIN